Published 1903

If Ontario native Robert Boyd had wielded a sword along with his pen, he might have attempted a revolution. He claimed his breakthrough method could be learned in one-fifth the time of the old systems, the proponents of which he accused of being "unscrupulous" and "evil," of following a crooked course and "enslaving the innocent." Followers of his system, meanwhile, "are the safeguard of truth and righteousness, and upon them we depend for the stability of our civilization." Shorthand is serious shit, people. Cross this guy's path with your bourgeois attitude and you'll find yourself short a hand.

Boyd certainly had his loyal fans. Multiple editions of the manual were published, along with a separate dictionary. The publisher of one of these wrote that he "believes as firmly as he believes his own existence, that fifty years from now (perhaps much sooner) Syllabic Shorthand will be in practically universal use to the absolute displacement of all other shorthand systems." And if imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Boyd would have been just tickled to see a curious manual called Chown's Shortime Shorthand show up in 1912, espousing a system only a tilt of the head away from identical to Boyd's.

Boyd certainly had his loyal fans. Multiple editions of the manual were published, along with a separate dictionary. The publisher of one of these wrote that he "believes as firmly as he believes his own existence, that fifty years from now (perhaps much sooner) Syllabic Shorthand will be in practically universal use to the absolute displacement of all other shorthand systems." And if imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Boyd would have been just tickled to see a curious manual called Chown's Shortime Shorthand show up in 1912, espousing a system only a tilt of the head away from identical to Boyd's.The schema for Boyd's Syllabic Shorthand reminds me of the Discomedusae illustrations in Kunstformen der Natur. Besides likeness in shape to the jellyfish, there's a similar obsession with symmetry. It's as if arranging the symbols into geometric shapes would make them a viable system, in the same way a jellyfish's radial arrangement produces a viable organism.

Boyd has taken up a most unnatural task, however: writing English using a syllabic script. Now, the syllable is an elusive entity. I had a linguistics professor whose life's work was on the syllable, but then again she was working with Georgian and syllables like prtskvna. The English syllable isn't quite so ambitious, but we have innumerable sequences like clamp, strict, and twelfths which no doubt constitute single syllables. Part of Boyd's confidence seems to come from his claim that "a syllable, according to its derivation from two Greek words, means the union of two or more letters in one sound." Phoneticians, weep.

Most of the "syllables" are vowel-consonant combinations like ag or od or il, meaning Boyd's system is closer to an abugida than a syllabary. There are also combinations like cr, sm, wh, and th (some of which are actually single sounds) that are given more or less arbitrary characters and counted in with the "syllables." If you ignore Boyd's terminology, his syllables do have some sense to them. This system is orthographic--based on spelling rather than underlying pronunciation--and Boyd is simply picking out pairs of letters that kinda go together sorta.

Let's make some words!

Would you look at that, they go together as easy as Tinkertoys, and kind of look like 'em too. The tricky part is getting your brain to register the shape of the character as the vowel and the orientation as the consonant. (I have a dyslexic friend who has trouble with letters like "b" versus "d" or "p" or "q", since you can rotate or flip them to become one another. Therefore, her instinct is not to differentiate them. She would hate Boyd Shorthand.) As a student of Gregg's system, I find it hard to remember each character as a syllable. My tendency, for the at character for instance, is to think of the short vertical stroke as the a and the long horizontal stroke as the t.

You might be thinking, "But what about all those words which start with a single consonant?" (Hush hush, says Boyd, that's the Dark Half of the English language. We try not to tread there.) What you do is take the consonant's corresponding e-syllable, the rounded hook, and shrink it.

Or, once you are advanced enough, you can omit this vestigial initial consonant entirely, scourge of the enlightened syllabic world that it is. I personally feel like the initial consonant is the most important factor in word identification, but I'll keep mum and keep my head.

With so many characters that double back on themselves, we end up with a lot of vague loops when one character attaches to another. In the examples, I follow the textbook illustrations, though the books give no explanation as to how the characters interact.

Early on in the books, you learn the word "honor," in which two circles overlap. I assumed that in the syllables oner the rounded hook of er would overlap in a similar way, creating an ambiguity. Fortunately, the given form for oner is distinct from onor, though I'm not sure why the circle of on becomes so tiny. The same kind of circle-shrinking happens when a circle attaches to a swirl (or "double-hook" as Boyd calls them). I wonder if theirs is the most consistent way to spell "wonder." How am I to differentiate ondr from ones?

Then there's the question of directionality. Although Boyd specifies which direction characters are to be written in, the logistics of attaching characters requires some improvisation. Below, y attaches below tr and the whole phrase is written upwards and rightwards. But, when a v intervenes, the tr is written in the opposite direction.

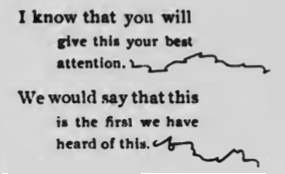

In general, it's difficult to avoid obtuse angles and uncomfortable joinings of curves and straight lines. Despite not technically lifting the pen during the suggested business phrases, I would find myself pausing at many of the junctures, probably longer than if I was lifting my pen. The next time you say the exact phrase "I know that you will give this your best attention," I have just the bent-pipe-cleaner-shaped pen stroke to record it.

Of course, every shorthand system has its quirks. Friction between the theory and the practice is inevitable, and a writer always develops personal conventions for troublesome forms. My only qualm is how Boyd, in his mission for simplicity, gives the impression that the system is entirely consistent and self-explanatory. He himself probably believed that with his syllable epiphany, he had broken through to the true, shimmering, seamless core of English phonology. He was reluctant to confront discrepancies with the realities of English because, as he believed, he had manifested the realities of English.

The sad truth is that awkward abbreviations abound to force words into syllabic compartments. The miniature consonants float like gnats through his dictionary, a messy glue between the pristine syllables. If you want to spell that clustered syllable twelfths, you use five characters: t-w-el-f-th, and drop the plural.

As poorly as Boyd Shorthand lived up to its creator's expectations, I admire that it took an entirely different angle from other systems. I like the bold Bauhaus geometry of it; my synesthetic side would say it's written in primary colors.

Writing in Boyd requires a peculiar mental contortion--it's kind of like eating lasagna with a ladle. That is to say, it can work, it's just like no way you've ever eaten before. Boyd has much potential as a secret writing system. Keep a scandalous diary in it, and even the most puritanical and cryptologically proficient of parents will be none the wiser. Who would ever write English in syllables?

A Canadian? A madman? A dreamer?

See a sample paragraph of Boyd Shorthand

Learning Materials

Boyd's Syllabic Shorthand, an Instructor and Dictionary (1904)

Boyd Shorthand (1912)

Boyd Shorthand Dictionary (1914)

No comments:

Post a Comment